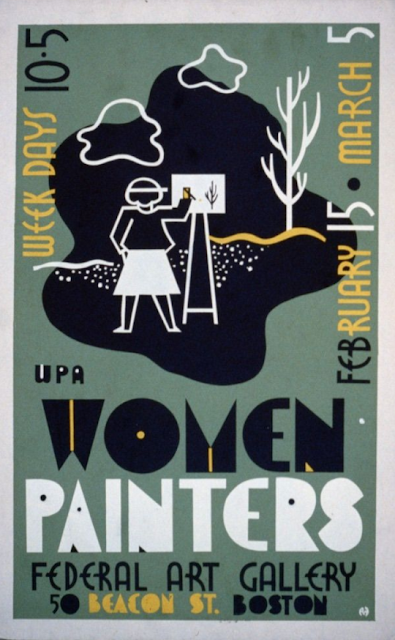

WPA art projects during the 1930s

|

| WPA Poster, n.d. |

Dr. Walter Heil, director of the de Young Museum in San Francisco, was selected as the regional director of the PWAP for Northern California, Nevada, and Utah.[4] In December 1933, Heil selected sixty Bay Area artists, including Helen Bruton, and called them to a meeting at the De Young Museum to be assigned their various projects. Although Helen was the only Bruton sister hired for the PWAP, she always intended to share the job with her sisters. Despite reports to the contrary, there were very few projects that the Brutons shared equally; there was always one sister in charge. As Helen pointed out, “We didn’t collaborate actually, but one would always be sort of standing by, to help if necessary. Marge would always help me if I needed her and vice versa. And the same way with Esther.”[5] Although Helen was in charge of the PWAP project, she relied on her sisters’ help; she was more than willing to share her minimal weekly payment with them. As she said, “I was the only one that was officially on the payroll, as you would say, and afterward, we divided that in three, so we didn’t exactly get wealthy over it, but we thought that was the fairest way to do it.”[6] Clearly the Brutons didn’t need this small stipend at all; one wonders if Helen didn’t feel just a little guilty about taking money out of the pocket of another artist who needed the funds more than she did. But for Helen, WPA projects weren’t about the money -- they were a unique opportunity for her to do something big in the art world, and she wasn’t going to miss out.

|

| Mothers House, San Francisco Zoo Photograph by the author, 2020. |

Helen’s first assignment was to create a mural on the exterior of the Mothers House at the San Francisco Zoo. The Mothers House, built in 1925, was originally part of the Fleishhacker pool complex, which was later donated to the city of San Francisco and became part of the zoo grounds. The ornate stone building, designed by San Francisco architect George W. Kelham, was built as a quiet retreat for mothers and children -- men were not allowed to enter. The artists Helen Forbes and Dorothy Puccinelli had been selected to paint murals inside the building, and Helen was assigned to decorate the exterior of the structure. The sisters identified two arched panels that seemed ideal for their murals.[7] As they discussed the design, Margaret came up with the idea of making the murals in mosaic, since they would be on the exterior of the building.[8] At first, Helen “hardly knew what [Margaret] was talking about -- that’s how sophisticated I was at that time.”[9] She said that “except for some little experiments that I had made, like a bird pool or a little thing like that, I hadn’t done anything big in mosaic.”[10] Despite her total lack of experience with the medium, Helen agreed that making the mural in mosaic was a good idea. Little did they know that Margaret’s innocent suggestion would send the sisters on an entirely new creative path; before long, they would be recognized as some of the most accomplished mosaic artists in California.

NEXT TIME: Making the mosaics on the Mothers House

[1] Charlotte Streifer Rubenstein, American Women Artists from Early Indian Times to the Present (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1982), p. 215.

[2] Rubenstein, American Women Artists, p. 215.

[3] Rubenstein, American Women Artists, p. 215.

[4] Oakland Tribune, Dec. 20, 1933, p. 4.

[5] Helen and Margaret Bruton, interview, Dec. 4, 1964.

[6] Helen and Margaret Bruton, interview, Dec. 4, 1964.

[7] Helen and Margaret Bruton, interview, Dec. 4, 1964.

[8] Helen and Margaret Bruton, interview, Dec. 4, 1964.

[9] Helen and Margaret Bruton, interview from New Deal Art Video Collection, de Saisset Museum at Santa Clara University, Feb. 26, 1976.

[10] Helen and Margaret Bruton, interview, Dec. 4, 1964.

Comments

Post a Comment